Evaluating Knowledge

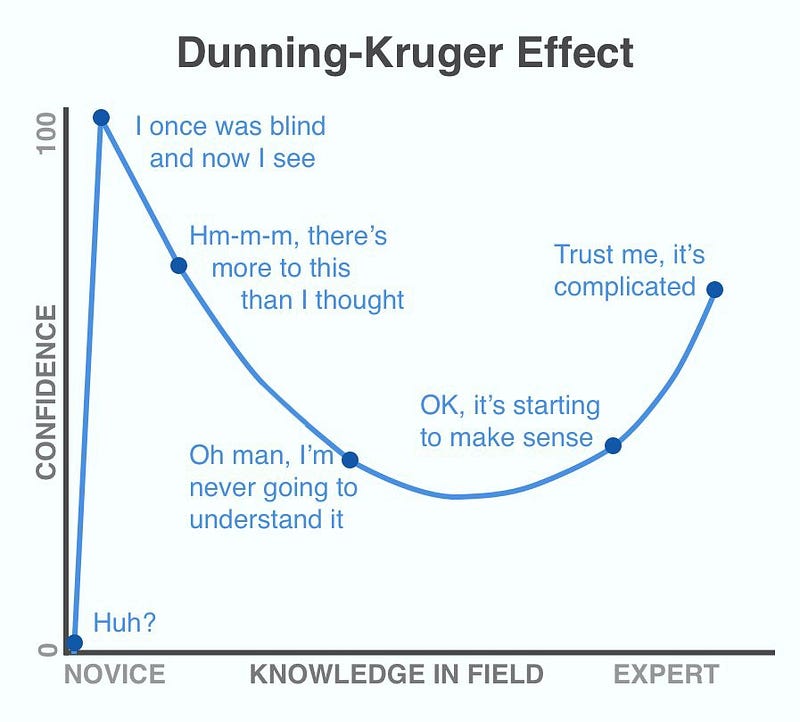

I often find myself reflecting: Where do I stand on the Dunning-Kruger scale? How do I evaluate my own knowledge compared to others? Do I sometimes overestimate what I know? Or do I underestimate myself? These questions might seem self-critical, but I’ve come to realize they’re essential for understanding myself and my biases.

For much of my life, I lived with impostor syndrome. No matter what I achieved, it felt insufficient. I’d convince myself that I didn’t know enough, that others were far ahead of me, and that I needed to work harder to catch up. Over time, this mindset became exhausting—a weight that many people carry without realizing it. If you’ve ever doubted yourself, you might relate.

It took me nearly a decade to recognize that I wasn’t giving myself enough credit. Accepting that my work had value wasn’t easy, but it was transformative.

How did I make myself believe that what I know is not worthless?

The Turning Point: Learning from Others

What helped me shift my perspective was conducting over 50 interviews for software engineering roles, from junior to senior levels. These interviews taught me a lot—not just about others, but about myself.

Some candidates with extensive experience struggled with seemingly simple tasks. For instance, about 80% couldn’t display a list of data during a 60-minute JavaScript exercise. I vividly remember one senior candidate, with 15 years in web development, who admitted they had never encountered the term “idempotence.” That got me a little disheartened because this is not domain-specific understanding or the deep knowledge of a certain technology. It is about: do you want to know and understand the things you are working with every day?

These moments made me reevaluate my own knowledge. They showed me that expertise varies widely, and that it’s okay not to know everything. Instead of being discouraged, I started to appreciate the things I did know.

The Value of Comparison

We’re often told not to compare ourselves to others, but I think there’s value in doing so—especially if you struggle with impostor syndrome. Our brains are constantly comparing our experiences with the world around us; why not apply that process to understanding ourselves?

Knowledge is measurable and, to an extent, comparable. Recognizing what you know (and don’t know) can help you find your strengths while staying grounded. The key is to avoid swinging to the opposite extreme—thinking you’re superior and have nothing left to learn. Staying curious and honest about your gaps is what keeps growth alive.

Embracing “I Don’t Know”

One of the most liberating lessons I’ve learned is the power of admitting, “I don’t know.” For many, there’s a fear of being judged for a lack of knowledge, but I’ve found that openly acknowledging uncertainty is not only relatable—it’s refreshing. It creates space for learning and encourages others to do the same. This phenomena had been studied under the name pluralistic ignorance.

Rather than pretending to have all the answers, I’ve made it a habit to say when I don’t understand something. It’s disarming, and more often than not, it leads to better conversations and collective growth.

Balancing Humility and Confidence

I’m well aware that there are people much smarter than me, and that there’s a vast universe of knowledge I’ve yet to explore. At the same time, I’ve come to appreciate that others can benefit from the knowledge and experience I do have.

Failing to do so flips the coin from embracing pluralistic ignorance to illusory superiority, where the individual believes they know the answers for basically everything, and surely those are the right answers.

Being humble doesn’t mean undervaluing yourself—it means staying grounded while recognizing your worth. True experience isn’t loud or boastful; it’s confident and measured. It acknowledges both the things you’ve mastered and the things you’ve yet to learn.

Ultimately, growth comes from finding balance: appreciating how far you’ve come, being honest about where you stand, and staying open to the endless opportunities to learn.

Staying humble does not mean you underestimate your worth, knowledge, and experience. True experience is humble and assertive.